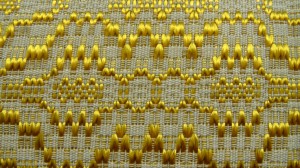

Despite being in the bottle for 30 years, the snake's body is perfectly preserved. Photo by Laima Vincė.

“Va, I found it!” Antanina exclaimed, bursting through the tiny cottage’s kitchen door, her deeply lined gaunt face flush with excitement. Her red and white cotton head scarf had slipped back from her forehead, revealing tousled strands of grayish-brown hair. Antanina triumphantly shoved a Soviet-era glass vodka bottle with a thick black snake curled up inside of it into my face. The snake was inert in amber-colored liquid. She twisted the bottle around meditatively, peered at it over her large owl-eye shaped, badly scratched plastic glasses, gave it a playful shake, and said, “See, the snake is perfectly preserved, like Lenin!”

Lina, Eglė, and I rose from our taborets and pressed our noses admiringly into the bottle. We fought back any revulsion we might have felt out of politeness and respect for this esteemed village verbal charmer and nodded gravely and approvingly at the perfectly preserved Lenin-snake.

“This snake has been inside this bottle for thirty years,” Antanina continued. “This Christmas it’s twenty years since my husband died, and it was about ten years before he died that he caught the snake, so that makes it thirty years. But look, she hasn’t rotted, not a single one of her scales has come off. That is how powerful the spiritas is.”

The snake lay as though it were sleeping with its slender head resting prettily in a curve over its back. Through the thick glass of the Soviet-era vodka bottle I could make out the outlines of each of its greenish-blackish scales.

“I’ll tell you what,” Antanina said, peering over her large round glasses at Eglė — a professor of indigenous religions at Nazareth College in Syracuse, New York doing field work for a scholarly article in English on Lithuanian indigenous healing practices — “I’ll pour some of this medicine into that glass Bobelinė bottle we emptied and you can take it home with you. Apply a few drops every day to that rash on your face. It will help. There was this woman who came to me once. She was skinny, skinny, all dried up, only bones were left. She said to me, ‘Give me some of your snake medicine.’ I did. I share with everyone. What’s it to me! I poured some into a bottle and she took it away with her. The next time I saw her she was plump and well.”

“Thank you Auntie,” Eglė said in her soft therapist’s voice.

Eglė was a gentle soul, tall and willowy with brown ringlets surrounding her face. For over a year now she had been struggling with a rash, covering it over just barely with facial powder. Eglė had an auto-immune system disease that potentially could become fatal. Her doctor in America had prescribed some very strong medication that Eglė was afraid to take because it was known to cause damage to the liver.

“It will help, I’m sure,” Antanina said, giving her head a shake so firm, her head scarf threatened to slip off altogether. Then she turned and slammed the bottle with the snake inside it down onto the kitchen table. Leaving the bottle standing between us, she poured us all another shot of her užpiltinė, made from cranberries she’d collected in the woods beyond her house and half a liter of moonshine from the neighbor. The word užpiltinė is derived from the verb užpilti, meaning to pour something on top of something else, in this instance a good brew of moonshine over delicious bittersweet berries.

“Let’s drink to Eglė getting better,” I suggested.

All the women around the table nodded in agreement. We eagerly downed our shots, slamming our shot glasses onto the small wooden kitchen table among jars of pickles, tea cups, tea, and our store-bought box of Paukščių Pienas chocolates.

“Sobirat folklore! ” Lina said and giggled, her face flush after her tenth shot.

Drinking on the job

We had not initially set out this morning to seek healing for Eglė. Nor had we planned on getting drunk with the subject of our interview on oral folk healing practices, 76-year-old Antanina. We had professional goals. Lina, who was a researcher at the Institute for Lithuanian Literature and Folklore, wanted to see if she could squeeze any more verbal charm formulas out of Antanina, whom she’d formed a bond with during her field work expedition in June. She also hoped she might get Antanina’s stubbornly silent and secretive neighbor, a more traditional verbal charmer, to reveal her charms on tape. I was conducting research for my novel, Broken Charms. One of my characters is a Lithuanian village charmer who flees the approaching Red Army, eventually ending up in America, where, to her horror, on foreign soil, her charms no longer work and she cannot save her from a terminal illness.

After we’d completed our recorded interview, we lingered, invited to a delicious lunch of hot country beet soup and boiled ribs. As we talked and shared our day with our “subject” our professional goals fell away and the urgency to heal Eglė grew.

“But tell me Auntie,” Eglė continued, “how did you get that large snake through that skinny narrow bottle neck?

“My husband was an engineer on the collective farm.” Antanina began, gearing up to tell a long story, “He was driving the tractor, doing some excavating. On the job site, in the sand, he dug up a large snake. He got down out of the tractor and picked up a branch with a fork in it,” she said, spreading two fingers into a V to show us.

“He took the fork and pushed down the snake’s head and stunned it senseless. That day through the kitchen window I saw him walking home with a big stick slung over his shoulder and a long thick snake hanging from it, swinging from side to side as he walked. He came into the kitchen and demanded, ‘Bring me a butilka!’ I rushed out to the shed and came back with an empty vodka bottle. He took the cork from the bottle and whittled slats into it, for air, you understand, so the snake could breathe. Then he took the snake off his stick and it came alive, slithering and writhing, shaking its stinger this way and that. He grabbed the head of the snake with his thick fingers and squeezed it just around its ears, holding it above the mouth of the bottle. The snake contracted and became skinny, skinny, skinny as my little finger. It slithered inside the bottle. Then my husband, capt, quickly popped on the cork.”

Antanina demonstrated the motion by slapping her palm onto the top of the bottle.

“He took some spiritas and poured it into the bottle through the slats,” she continued. “He poured just enough that the snake could keep her head above the spiritas and not drown in it. Then, the snake began knocking around the glass. Every time she hit against the glass, she’d release a white poison into the spiritas, turning it milky white. Whenever she calmed down, my husband would tap the bottle with his thumb and fore finger and she would jump and let out the poison again. She lived in the spiritas for a long time and then she died.”

Antanina paused her talk to fill our shot glasses once more. “Okay girls,” she said. We had no choice but to obey, Sobirat folklor!

We’d drifted away from interviewing earlier that morning when after a few hour’s talk, Eglė asked if Antanina could say a charm to help heal the incurable rash on her face.

“My child,” Antatina said, “you can do it yourself. All you have to do is say a charm over your face cream! You make the sign of the cross over the face cream, you say the charm, you say your name, you make the sign of the cross again and you put it on your face.”

“Really?” Eglė gasped.

“It does make sense,” Lina said, leaning over the coffee table towards me and Eglė. “If you charm butter to cure the Rose and you charm salt to charm away an evil wind, why not then charm face cream?”

A knock on the door interrupted us. A shy, awkward, tall young woman wearing a head scarf poked her head inside.

“Come in Rasa,” Antanina called out in a friendly voice.

But the girl only took one hesitant step, then quickly retreated when she saw us.

“Excuse me,” Antanina said and rushed out of the room. She reached above her cupboard for a carton of cigarettes and handed it to the girl. The girl crammed her skinny arm into her pocket and yanked out a few grimy bills and handed them to Antanina. The two walked into the kitchen. From around the corner I saw Antanina pick up a magazine and open it up. She wrote something down on a sheet of paper inside, then shut the magazine, and hid it in a cupboard.

“The border with Belarus is so close here,” Lina whispered, “she must be getting cheap cigarettes illegally from over the border. They could practically toss them over the bushes to her.”

“She has to live somehow,” Eglė said.

“She’s very generous though,” Lina continued. “last time I was here she gave me four charms. I’ve got them written down right here, in this notebook.” Lina held up the notebook for us to see and then pulled it back possessively.

Antanina came rushing back into the room, “Girls, it’s one o’clock, make yourselves at home, I’m going out to milk my cow, Žibutė.”

“Can I help you? Drive you to the pasture?” I asked.

“No!” Antanina exclaimed, waving her gnarly hand, “I’ll take my bicycle.”

“Village of idiots”

Although Antanina was 76, she was as spry as I was. With quick little steps on her short bow legs she trotted out of the room and we three women were left to our own devices. A dangerous thing, leaving three researchers unattended in a charmer’s house.

I watched through the white knit-lace curtains as Antanina climbed onto her purple bicycle and pedaled off, a milk can dangling from the handlebar.

Lina, Eglė, and I immediately made for the glassed-in porch where Antanina had left piles of her woven blankets set out on the windowsill, others hanging from a clothesline. We opened up the blankets, examined the patterns, the combinations of color, looking closely at the tightness of the weft. We established that not only could this magical woman heal, she was a weaver of the highest caliber in the old tradition.

By that time I was finding it hard to believe that I’d only met Lina and Eglė this morning when I’d pulled into the parking lot of the Institute for Lithuanian Literature and Folklore in Antakalnis. At nine sharp, despite the heavy rain that was only just tapering off, Lina was already waiting for me in the parking lot. Eglė quickly joined us, emerging from inside the building.

“We are heading to the village of Milkuškos in the Švenčionys region,” Lina explained as I pulled out of the gated parking lot onto Antakalnis Street.

Švenčionys is a town 84 km from Vilnius surrounded by of fir forests and farmsteads and fallow fields situated along the border with Belarus. Incorporated into Poland in the early twentieth century and for a brief period in 1939-1940 a part of Soviet Belarus, Švenčionys was now Lithuanian, though just barely. The Švenčionys region was made up of a mix of diverse multicultural villages inhabited by Polish, Lithuanian, Belarusian, and Russian-speaking people — few of whom could claim one of those nationalities exclusively. Most families were mixed. The average citizen of the region spoke, read, and wrote all four languages fluently regardless of education.

During the reign of Vytautas the Great in the 15th century, the area served as Vytautas’s manor. Vytautas the Great personally settled Tatar craftsmen and tradesmen in Švenčionys. He also established the town’s first church in 1414. By 1486 the town was officially named, but Švenčionys only received town status in 1800. By 1812 the armies of Napolean Bonaparte and Napolean himself passed through the town and its surrounding thick pine forests. It is believed that Švenčionys was named for a nearby lake called Šventa, which means holy in Lithuanian, marking Švenčionys as a holy place on the Lithuanian folkloric map.

“The village was formerly called Samadūriškės,” Lina continued as we turned off of Antakalnis Street and onto Nemenčinės Road. She waited for my reaction and when she didn’t get one she burst out laughing, doubling over in the front passenger seat.

I looked over at her confused.

“The name literally means, ‘village of idiots,’” Lina explained. “It’s a name that’s typical of the combination of Lithuanian and Russian unique to this border region. ‘Sama’ in Russian means ours; “dura” means idiot, and then you tack on a Lithuanian ending ‘iškės’. Anyway,” Lina continued, after she’d recovered from laughing over her own joke, “the charmer we are going to visit first heals absolutely everyone in that village.”

When we arrived, Lina counted off the houses leading up to Antanina’s trim yellow wooden house. As I carefully negotiated the wet dirt road, up ahead we saw a young blond couple in their early twenties pushing a stroller. They were dressed in ragged clothing and had that hunched-over downtrodden look of young people who couldn’t escape the village. There was a baby in the stroller and a tow-headed toddler boy trotting beside it. The family stopped in front of Antanina’s house. The woman headed down the driveway to house and the toddler trotted off behind her.

“They must be her grandchildren,” I said, thinking out loud.

We got out of the car, collected our recording equipment, notebooks, and cameras and headed over to the house. As we turned into the drive way, the little boy we’d seen from the road, a tow-headed blue-eyed darling, came trotting down the driveway gleefully holding out a carton of cigarettes, eager to hand them over to his father, who was waiting at the top of the driveway with the baby in the stroller. We ran into the boy’s mother in the doorway. We greeted her, but she averted her head.

“Laba diena, laba diena,” Antanina shouted in genuine delight when she saw us with Lina. She came steaming out of the little wooden cottage dressed in an orange, brown, and yellow plaid cotton skirt, a lavender cotton tank top, and a red and white cotton head scarf. There was a cross on a gold chain around her neck. “Come in, come in,” she said, leading us through her kitchen, through her bedroom, and into the living room.

The living room was dominated by a large cylindrical metal buržuika that heated the entire house in the winter. It was an efficient method of heating: a pipe funneled the heat from the buržuika into the other room where special ceramic tiles lined an entire wall keeping that section of the house warm. On the opposite side of this wall that same heat was used to fuel the old-fashioned cooking stove in the kitchen. The entire operation could run on just a few logs all day long.

All the sofas and chairs were covered with Antanina’s woven bed spreads, the color scheme of choice being red and white. In the corner over the sofa on the yellow-painted plaster walls hung two holy pictures: one of Jesus Christ with a large red heart in the center of his chest and one of a peasant girl with a lamb on her knees before the Virgin Mary with the Šiluva church in the background.

Saved by charm

We sat down, the four of us women, Eglė and I on the sofa, Lina on a chair with Antanina beside her. Lina set up the recording equipment she had brought with her from the Institute and I set down my tape recorder on the table.

“If a person wants to learn the charms,” Antanina began, “then they absolutely should. God hears your words. Your words can help others. My neighbor keeps her words secrets. But I don’t agree. I share my words with whoever asks me for them.”

“Though, isn’t it true that charms can only be passed to the firstborn or the lastborn,” I asked.

“That’s right,” Antanina nodded her head in agreement. “I am my mother’s firstborn. But no one taught me the charms directly. When my mother and my father died, I was cleaning out their house. Among the books I found a sheet of paper. On that paper, written in Lithuanian but with Polish letters, I found four charms. My mother had written down those words for herself: a charm to cure the Rose; to protect against evil wind; to cure snake bite; and for hernia. I deciphered those charms and I learned to heal with them. There was one woman who I’d cured from the Rose. She saw me after church and came up and said to me, ‘I bought you a box of chocolate, but I forgot to bring them with me today.’ I told her, ‘I don’t need your candy. If a person needs help, I will help them.’”

“Who was your first patient?” I asked.

“I remember healing a horse’s foot with lard and a charm first. A woman came with a horse and the horse had a wound on its leg. I put some lard on the horse’s leg and said the charm and the leg healed. There was a man who was planting potatoes out in the wind. A woman passed by and said, ‘Oh, what a horse have there, you don’t have to do anything for it. What a good horse.’ Immediately the horse went wild and became sick. They came to me with the horse. I healed that horse too. Later, I ran into them in Švenčionys. They told me their horse was doing well. Their cow had gotten the evil eye and had stopped giving milk. I healed the cow and now it is giving milk. They wanted to give me money, but I said ‘absolutely not.’ I said, ‘If you like, you may offer the money to the church.’ That’s what they did.”

“Why don’t you take money for your healing?” I asked.

“What do you think I am, some sort of a burtininkė [magician], one of those types who takes money for fortune telling with cards! Oh no, never, that’s not me,” Antanina raised her voice in indignation. “If someone needs help, then I absolutely must help them. It would be wrong to take money for healing a person or an animal.”

I remembered the wichasa wikan or holy man from John Fire and Richard Erdoe’s oral history of the Lakota tradition, Lame Deer: Seeker of Visions. According to Lame Deer a true healer never took money for their healing, although they could accept gifts but not expect them.

Antanina then launched into a long involved story about how her daughter fell into the clutches of an ekstrasensė, [ESP healer], the type who use extrasensory perception to heal any ailment from cancer to heart attack.

“Immediately the woman demanded 300 litai,” Antanina said, “and I paid her. This woman had crosses hanging all over her mirrors as though she were so religious. Then she took my daughter on the highway to Kaunas. They stopped at that place alongside the highway where there is high electrical voltage. The woman made my daughter lie down under the electrical wiring. She flapped her arms around, muttering some sort of nonsense. She was dressed all in white. Then, she took my daughter to stay in a place in Druskininkai. We kept bringing my daughter food there, but she just kept getting worse and worse. We cooked cepelinai, šašlykai, but she wouldn’t eat. Then she stopped talking. ‘My child, for God’s sake, let’s go home,’ I said finally. ‘But the others will die without me,’ she said, meaning a man who was sick and weak and was staying in Druskininkai with her. So we took him back with us too. We brought that man to our house; heated up the sauna; treated him like a guest, as though he were one of our own. Then we took him back when he asked us too. But, we saw that he wasn’t well, so we called the ambulance. The ambulance took the man to Vilnius. Within two days he died. The doctors told us that the man had cancer.”

Antanina waved her hand in a gesture of disgust, “I heal all sorts of skin ailments, I heal from the evil wind, from snake bite,” she said, “but even I couldn’t heal cancer.”

“What do you think about when you say a charm?” I asked.

“I just think about the holy words and about God helping the sick person and that’s it. That’s all I think,” Antanina said, glancing up at the two holy pictures on the wall in the corner. “Once I was in Vilnius visiting. My granddaughter was crying out, ‘The evil wind has gotten me, Grandmother, I’m so sick.’ I went to her and I charmed away the wind. Then I sat down and I wrote down the holy words for her, so that she could take care of herself. The most important thing is to believe in the words and to believe in God. When my husband was in the hospital for his heart he called me and couldn’t even talk through the pain. He’d gone out into the hallway to have a cigarette and caught a shiver. I was certain that the evil wind had cut him. I went to the hospital and saw the doctor. My husband’s tongue had curled back into his mouth and that was why he could not talk on the phone. I called a neighbor who knew good charms. She drove to Vilnius and said the charms. He got better. The doctor was amazed. ‘Did he have this before?’ the doctor asked. ‘No,’ I told the doctor. I stayed and slept with him. Whenever his tongue curled up, I’d say the woman’s words. I healed him. The doctor stood there with a gaping mouth and couldn’t do a thing for him and so I healed him. Without the charms he would have died.”

Again we were interrupted. This time by a middle-aged Russian woman who stopped by. Antanina rushed out of the room and quickly completed her cigarette transaction, then hurried back and picked up her story where she had left off.

Evil eye, evil wind

“Our šviogeris [brother-in-law] came to visit from Belarus. There was a party,” Antanina continued, “he went outside to smoke. All of a sudden, he began tearing at his clothes, shouting, ‘I feel bad, bad, bad.’ There was a neighbor who knew exactly what had happened. She said immediately, ‘It’s the evil eye.’ She ran and got some salt and said the words and washed out his eyes. He was healed immediately and could come back to the party.

“Tell me,” I asked, “What is the evil eye?”

Antanina furled her brow. “A person can get very sick from the evil eye,” she said, “very sick. Someone sees a beautiful woman and then all of a sudden they feel very bad, very sick. It’s the evil eye. A cow might be giving good milk and then all of a sudden stops. Someone saw the cow and gave it the evil eye. It’s when a person sends evil thoughts in your direction.”

Antanina leaned in towards me, “Now you’ll know how dangerous the evil eye is.”

“Can anyone give an evil eye?” I asked.

“It can happen very quickly,” Antanina said. “Someone sees a person and sends a bad thought and that person gets sick. The person who sends the evil eye is not necessarily a bad person. Something happens and very quickly and that’s all.”

“What does it mean to be sick from the wind?” I asked.

“The wind blows and a person becomes paralyzed,” she answered.

“Is it like catching cold from the wind?”

“Absolutely not. In a moment the wind blows and a person gets sick. The evil wind blew onto him.”

“And what about the Rose?”

“The leg is swollen and itches for example. The doctors can’t heal it. They say, ‘Go to the bobutės [old ladies].’ I was in Druskininkai and my neighbor was there. He was a brigade leader and he ended up in the Hospital for Infectious Diseases. What happened? He was lying in the dirt and rubbed one leg with the other. He went home and soon had a fever of 40. They hospitalized him. It was the Rose. All the doctors said so. He was there a week and no one could help him. The neighbor said to me, “Go and take care of him.’ I went. I bought some butter and I charmed it. I applied the butter to the rash and I told him not to go anywhere. I came back the next day and he stepped out into the hallway, healed. It was all over. What’s the point of staying in the hospital if there isn’t anyone there who knows how to cure the Rose?”

From the Rose we move onto the topic of snakebite.

“If we go out into the woods to collect cranberries, there are lots of snakes,” Antanina said, “I tell my granddaughters, ‘I’ll say a charm and we won’t see those parasites.’ There’s so many, you put down your basket and they crawl inside. Out in the fields, a snake will strike a cow in the leg. The cow collapses. If you see it in time and get a charmer to say a charm over the cow, then the cow will get better. Otherwise, it will be dead by nightfall.”

“Do you teach your granddaughters to charm?” I asked.

“I’ve told my elder granddaughter. My sister in Šakiai is the lastborn. I told her the charms. ‘We don’t do that here,’ she said. ‘Have the charms for yourself,’ I said. My other daughter, she doesn’t learn them, but my granddaughter is interested.”

Eglė said, “I’d like to learn. I’m the eldest in my family.” Then she added, “You are very inclined to sharing your charms. You are generous.”

“I don’t know what I am,” Antanina stated matter-of-factly. “Let me go check our soup.” She stood and rushed out of the room.

When she was gone, Lina whispered to Eglė, “I’m sure she’ll give them to you. But I’m not sure about you,” she said to me.

“Right, I’m a middle child,” I said. “I don’t have any claim on the charms.”

The secret

“I’ll go and look for that paper,” Antanina called from the other room.

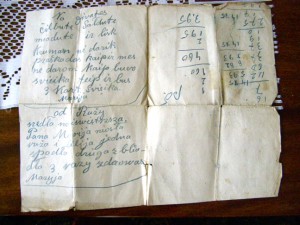

We heard a few drawers banging around and Antanina returned with a folded sheet of yellow paper in her hands. She set the paper down on the coffee table in front of Eglė. In blue pencil, in shaky large loopy handwriting, there were the charms, written out like poetry in short compact lines.

“Oh!” Eglė clapped her hands together in glee, “the magical document!”

“Let me get my other glasses,” Antanina said, reaching for an identical pair of owl-eye shaped glasses and settling them on top of the glasses she was already wearing.

“Auntie,” Eglė said in a voice full of reverence, “will you allow me to write the words down.”

“Of course,” Antanina said.

Eglė’s face lit up and she eagerly reached for her notebook. “Auntie,” she said, “your voice is so lovely. Could you please read the magical document out loud.”

Antanina leaned in over the paper. “Od poruszenie,” she read the words in Polish. “That is for hernia.”

“Please read it,” Eglė breathed.

Antanina read slowly, through her dialect speaking the cadences of the text, an odd mixture of Polish and Lithuanian:

Žadu aš porušene

ne aš: Panale Svenčiausia

ariotas apaštalai 3 kart s m.

(I charm for hernia

not I: The Holy Miss

angels the apostles)

The “3 kart s m” was an abbreviation for: say the Hail Mary three times. Most verbal charms end with instructions to say the Hail Mary three times.

Then Antanina opened up the brittle piece of paper. On one side there were two more charms. On the other, upside down, were a column of digits, obviously someone’s scribbled calculations.

“This is for snakebite,” Antanina said.

Čilbute Saldute

Miadute ir lisk

Kruman nė darik

Praškados kaip ir mes

Ne darom kaip buvo

Sveika teip ir bus

3 Kart. Sveika Marija

“Oh my,” Eglė called out, “listen to those cadences, hear the rhyme, this is pure poetry. How beautiful.”

Eglė leaned over the paper, copying the words into her notebook, gingerly pulling it towards her, handling the magic document with reverence.

“Thank you so much for sharing this magical document,” Eglė breathed.

“Are there any charms for sickness of the spirit?” I asked.

“Oh my child,” Antanina said shaking her head, “I’ve never heard of any.”

That made me wonder whether sicknesses of the spirit wasn’t purely a twenty-first century phenomenon.

“Tell me Auntie,” Eglė said, leaning in towards Antanina, “Any there any charms to ward against bad men?”

“No,” Antanina said in a serious tone, “None.”

“After independence they put up the border,” Antanina said, changing the subject, pointing out the window at the guard tower in the bushes at the end of her backyard. “You see the guard post outside my window. Now it’s not so easy to travel over there to Belarus. You need a visa. It’s expensive. I can’t get the thread I use for my weaving. I’ve used it all up and they don’t sell it in Lithuania, only in Belarus. We can’t go to those village where we used to dance and have friends. It’s only a kilometer away, but we can’t go. There’s a guard tower over there now and they watch us. It used to be, they’d come over with cigarettes and vodka — what’s a kilometer? When the Russians were here there was no border. We were Lithuanians and a stone’s throw away they were Belarusians. We all danced together. We lived together. Many of our neighbors speak Belarusian. We have no problems getting along.”

“The last time I was here,” Lina said, “you told us that you had to go speak to the priest in Švenčionys about your charming.”

“The neighbors were angry with me,” Antanina said. “They said I was committing a sin, that I was performing magic. My neighbors told me to go to confession. I went to talk to the priest about it. ‘It’s nothing,’ the priest said, ‘what’s so bad about it — you are saying prayers, holy words.’ I told him I don’t cheat anyone or take anyone’s money. ‘So, what, if they want to give you a donation, what of it?’ he told me. Those same neighbors come to me when they have a problem. They call it magic, but it’s not magic.”

Once the soup had sufficiently boiled, Antanina sat us down to lunch. But what was lunch without a little spiritas for the digestion? One digestive drink led to another and soon we were taking turns conjuring up curative toasts, shouting out sobitrat folklore! in chorus after every one. And that was how we came to be seated at this village charmer’s small wooden kitchen table with a snake in a vodka bottle standing between us.

“Will you stay longer if I heat up the sauna,” Antanina asked.

Eglė’s face lit up. The focus of her PhD dissertation had been on rituals associated with the sauna.

“I wouldn’t mind,” I said, gazing out at the cold rain droplets pattering down the window panes, “if Lina and Eglė agree.”

“I would like to go in the sauna,” Eglė said.

“I recently had an operation for my varicose veins,” Lina said, “so I’d rather not, but you two go ahead.”

“It will take an hour and a half for the sauna to heat up,” Antanina said.

“We have time,” I said.

I was calculating in my head how long it would take for me to sober up so that I could safely make the drive back to Vilnius. The sauna would help me sweat the alcohol out of my system.

A pile of wood outside Antanina's house. Many rural Lithuanian homes are heated by wood burning. Photo by Laima Vincė.

“Good then,” Antanina said and stood from the table. She led us outside to the sauna, a rough wooden shack beside the house. Antanina and I went out to the woodshed to gather armfuls of firewood to heat the sauna. I was glad for the physical work. Since I’d left my house on Peaks Island, Maine two years ago, I’d not stoked a wood stove. Antanina tried to treat me like a guest and stop me, but I insisted and got my way. We shoved the logs inside the stove, lit them, while I stacked the others close by, on hand to keep the stove at a hot even temperature once the sauna was ready. Antanina filled the metal tub built onto the side of the country stove with water. Attached to the metal tub and the masonry stove was a large metal basket filled with stones. Once the stove grew hot enough, it boiled the water, which warmed the stones. Then, one ladled hot water over the stones to create the steam that had curative properties.

Saunas work, but do folk remedies?

As two hours passed and the women lost themselves in more and more talk, I took it upon myself to be the one to run out into the rain and stoke the stove in the sauna. When the sauna was finally steaming hot, I told Eglė and we both went outside. We undressed in the small room outside of the sauna and entered together naked into the steam. We sat on the wooden benches, allowing our bodies to drink in the heat. Whenever the room seemed to cool, one of us rose and poured a ladle of out water over the stones, setting them off steaming and hissing and crackling. Then Eglė picked up the vanta, a broom made up of birch leaves, and beat my arms and legs and back, and then I beat hers.

“This skin rash, this is not a disease that will go away when the symptoms are treated, this is a disease that comes from deep within and which will be healed when I face it,” Eglė told me.

I listened, knowing that I had my own difficulties to face. Only I had not been brave enough to ask for the healing today. Eglė had.

Eglė and I poured cold water on our faces, on our necks, our breasts, our legs, and arms. We breathed in the good steam and I knew although it would still take some work and time, possibly a long time, the healing would come.

I returned home with the good energy from our day together with the healer and lay content between my flannel sheets. I sent a friend a text message: I’ve had the most beautiful day today for no other reason than to spread that good energy I’d brought back to Vilnius with me by passing it on to others.

The next morning I popped in to say hello to my neighbor across the hall, Jolanta, whom I was friendly with. I told her about my day of healing and about the snake in the vodka bottle. Jolanta waved her manicured hand at me and said dismissively, “Oh, Laima, everybody has a snake in a vodka bottle in their closet. We had one for years in our cabinet until someone finally threw it away.”

For reasons of privacy, one of the names in this essay has been changed. Laima Vincė, a New York native, is a Lithuanian-American non-fiction and children’s book author, Fulbright scholar in creative writing at Vilnius University, journalist, memoirist and translator. For more information about her work, visit her website at www.laimavince.com and to order her acclaimed memoir “Lenin’s Head on a Platter” go here. Two translations she did of Lithuanian authors can be found here and here.

Disclaimer:

Views expressed in the opinion section are never those of the Baltic Reports company or the website’s editorial team as a whole, but merely those of the individual writer.

Briusly baras has a snake vodka as well, Check it out.

It cures a lot of ailments. :)

Really nice story, thanks for sharing :)

Hello, looking on Google for Snake wine information I found your website, do you have anything more posted here related to Snake wine liquor ?

Snake wine is shown there:

http://www.asiansnakewine.com/

I previously bought a snake wine I am now looking for any other creature wine as mice or tokay, any idea where to find ?

Thanks a lot for your help.