RIGA — With chunks of ice floating on the Daugava past my window and out to a quiet disappearance under Baltic waves, it’s the perfect time of year to remember my favorite Latvian artist, Vilhelms Purvītis.

Born in 1872 and dying in 1945, Purvītis remains pretty well-known in Latvia, though he is not accorded the preeminent status of his friend Jānis Rosenthals and lacks the cult following of his pupil Kārlis Padegs who possesses the requisite tragic biography as well as a [private_supervisor]style of draftsmanship that remains shockingly modern. Anyone who likes the graffiti art of Banksy should check out Padegs.

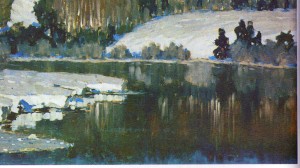

But returning to Purvītis, though his style did evolve through the years — a pat description would be a sort of hybrid of Friedrich and Monet, though this does him no justice — it was never less than technically superlative. His experiments with expressionism seem less successful in my opinion than his rigorous, almost two-dimensional landscapes.

Prominent in those landscapes is water, an element over which Purvītis had complete mastery, and this is why the sight and sounds of melting ice, swollen streams and dripping branches summon him into my mind.

Purvītis discovered that there is no such thing as snow, just water in various different states of being. This is actually a more profound insight than it sounds and explains why Purvītis strikes me as being if not the greatest Latvian painter then certainly the greatest painter of Latvia. In this land which spends the greater part of the year having snow, sleet, rain and fog fall upon it and where lakes, streams, rivers, swamps, marshes, puddles and ponds splash and ooze ceaselessly from one to the other, there is an underlying fluidity and infinite variability in water and all of its forms that cannot be captured in a simple field of white or blue color.

Purvītis landscapes are not covered with snow. Lakes do not sit in the landscapes. The snow and the water are integral elements of the landscape, just as worthy of attention as the forest, hill and foliage.

The snow of Purvītis’ winter landscapes is never static. It is either accumulating or freezing or melting. It is always between two states, never possessed by one alone. In the spring landscapes which are probably his greatest works, the snow doesn’t just disappear. Like an occupying army it kids itself it is making a strategic withdrawal, not experiencing a defeat. It pulls back gradually, grudgingly releasing sods of earth and tufts of rough grass that then start their own process of seasonal transformation and reappear in his summer and autumn pictures in quite different guises.

Purvītis’ work strikes me as very human. We tend to react to artists we like in one of two ways: they either show us the world in a way we have never seen before (these tend to be the ones hailed as geniuses) or they offer us the world in a way that gives us a sense of deepened familiarity and reality. I think Purvītis belongs to the second category. I think it also gives his work a sense of tremendous humanity, even though figures rarely feature.

Purvītis’ greatest gift to Latvian culture may have been his work establishing the first Latvian art academy and the training he gave to numerous younger artists including Padegs and another of my favorites, Pēteris Krastiņš, whose biography was even more tragic than Padegs’ — Krastiņš ended up being shot by the Germans when they decided to liquidate the mental hospital in which he was a resident.

As with many of his contemporaries, many of Purvītis’ works were lost or destroyed during the Second World War. However, a couple of rooms of his work are on permanent show at the Latvian National Museum of Art. Though poorly-lit (if only Latvia had a Kumu) they are worth the small entrance fee in their own right.

Completely lacking ego and ostentation, Purvītis’ work is out of step with the modern age. That may be why I find it so enjoyable and satisfying. [/private_supervisor] [private_subscription 1 month]style of draftsmanship that remains shockingly modern. Anyone who likes the graffiti art of Banksy should check out Padegs.

But returning to Purvītis, though his style did evolve through the years — a pat description would be a sort of hybrid of Friedrich and Monet, though this does him no justice — it was never less than technically superlative. His experiments with expressionism seem less successful in my opinion than his rigorous, almost two-dimensional landscapes.

Prominent in those landscapes is water, an element over which Purvītis had complete mastery, and this is why the sight and sounds of melting ice, swollen streams and dripping branches summon him into my mind.

Purvītis discovered that there is no such thing as snow, just water in various different states of being. This is actually a more profound insight than it sounds and explains why Purvītis strikes me as being if not the greatest Latvian painter then certainly the greatest painter of Latvia. In this land which spends the greater part of the year having snow, sleet, rain and fog fall upon it and where lakes, streams, rivers, swamps, marshes, puddles and ponds splash and ooze ceaselessly from one to the other, there is an underlying fluidity and infinite variability in water and all of its forms that cannot be captured in a simple field of white or blue color.

Purvītis landscapes are not covered with snow. Lakes do not sit in the landscapes. The snow and the water are integral elements of the landscape, just as worthy of attention as the forest, hill and foliage.

The snow of Purvītis’ winter landscapes is never static. It is either accumulating or freezing or melting. It is always between two states, never possessed by one alone. In the spring landscapes which are probably his greatest works, the snow doesn’t just disappear. Like an occupying army it kids itself it is making a strategic withdrawal, not experiencing a defeat. It pulls back gradually, grudgingly releasing sods of earth and tufts of rough grass that then start their own process of seasonal transformation and reappear in his summer and autumn pictures in quite different guises.

Purvītis’ work strikes me as very human. We tend to react to artists we like in one of two ways: they either show us the world in a way we have never seen before (these tend to be the ones hailed as geniuses) or they offer us the world in a way that gives us a sense of deepened familiarity and reality. I think Purvītis belongs to the second category. I think it also gives his work a sense of tremendous humanity, even though figures rarely feature.

Purvītis’ greatest gift to Latvian culture may have been his work establishing the first Latvian art academy and the training he gave to numerous younger artists including Padegs and another of my favorites, Pēteris Krastiņš, whose biography was even more tragic than Padegs’ — Krastiņš ended up being shot by the Germans when they decided to liquidate the mental hospital in which he was a resident.

As with many of his contemporaries, many of Purvītis’ works were lost or destroyed during the Second World War. However, a couple of rooms of his work are on permanent show at the Latvian National Museum of Art. Though poorly-lit (if only Latvia had a Kumu) they are worth the small entrance fee in their own right.

Completely lacking ego and ostentation, Purvītis’ work is out of step with the modern age. That may be why I find it so enjoyable and satisfying. [/private_subscription 1 month] [private_subscription 4 months]style of draftsmanship that remains shockingly modern. Anyone who likes the graffiti art of Banksy should check out Padegs.

But returning to Purvītis, though his style did evolve through the years — a pat description would be a sort of hybrid of Friedrich and Monet, though this does him no justice — it was never less than technically superlative. His experiments with expressionism seem less successful in my opinion than his rigorous, almost two-dimensional landscapes.

Prominent in those landscapes is water, an element over which Purvītis had complete mastery, and this is why the sight and sounds of melting ice, swollen streams and dripping branches summon him into my mind.

Purvītis discovered that there is no such thing as snow, just water in various different states of being. This is actually a more profound insight than it sounds and explains why Purvītis strikes me as being if not the greatest Latvian painter then certainly the greatest painter of Latvia. In this land which spends the greater part of the year having snow, sleet, rain and fog fall upon it and where lakes, streams, rivers, swamps, marshes, puddles and ponds splash and ooze ceaselessly from one to the other, there is an underlying fluidity and infinite variability in water and all of its forms that cannot be captured in a simple field of white or blue color.

Purvītis landscapes are not covered with snow. Lakes do not sit in the landscapes. The snow and the water are integral elements of the landscape, just as worthy of attention as the forest, hill and foliage.

The snow of Purvītis’ winter landscapes is never static. It is either accumulating or freezing or melting. It is always between two states, never possessed by one alone. In the spring landscapes which are probably his greatest works, the snow doesn’t just disappear. Like an occupying army it kids itself it is making a strategic withdrawal, not experiencing a defeat. It pulls back gradually, grudgingly releasing sods of earth and tufts of rough grass that then start their own process of seasonal transformation and reappear in his summer and autumn pictures in quite different guises.

Purvītis’ work strikes me as very human. We tend to react to artists we like in one of two ways: they either show us the world in a way we have never seen before (these tend to be the ones hailed as geniuses) or they offer us the world in a way that gives us a sense of deepened familiarity and reality. I think Purvītis belongs to the second category. I think it also gives his work a sense of tremendous humanity, even though figures rarely feature.

Purvītis’ greatest gift to Latvian culture may have been his work establishing the first Latvian art academy and the training he gave to numerous younger artists including Padegs and another of my favorites, Pēteris Krastiņš, whose biography was even more tragic than Padegs’ — Krastiņš ended up being shot by the Germans when they decided to liquidate the mental hospital in which he was a resident.

As with many of his contemporaries, many of Purvītis’ works were lost or destroyed during the Second World War. However, a couple of rooms of his work are on permanent show at the Latvian National Museum of Art. Though poorly-lit (if only Latvia had a Kumu) they are worth the small entrance fee in their own right.

Completely lacking ego and ostentation, Purvītis’ work is out of step with the modern age. That may be why I find it so enjoyable and satisfying. [/private_subscription 4 months] [private_subscription 1 year]style of draftsmanship that remains shockingly modern. Anyone who likes the graffiti art of Banksy should check out Padegs.

But returning to Purvītis, though his style did evolve through the years — a pat description would be a sort of hybrid of Friedrich and Monet, though this does him no justice — it was never less than technically superlative. His experiments with expressionism seem less successful in my opinion than his rigorous, almost two-dimensional landscapes.

Prominent in those landscapes is water, an element over which Purvītis had complete mastery, and this is why the sight and sounds of melting ice, swollen streams and dripping branches summon him into my mind.

Purvītis discovered that there is no such thing as snow, just water in various different states of being. This is actually a more profound insight than it sounds and explains why Purvītis strikes me as being if not the greatest Latvian painter then certainly the greatest painter of Latvia. In this land which spends the greater part of the year having snow, sleet, rain and fog fall upon it and where lakes, streams, rivers, swamps, marshes, puddles and ponds splash and ooze ceaselessly from one to the other, there is an underlying fluidity and infinite variability in water and all of its forms that cannot be captured in a simple field of white or blue color.

Purvītis landscapes are not covered with snow. Lakes do not sit in the landscapes. The snow and the water are integral elements of the landscape, just as worthy of attention as the forest, hill and foliage.

The snow of Purvītis’ winter landscapes is never static. It is either accumulating or freezing or melting. It is always between two states, never possessed by one alone. In the spring landscapes which are probably his greatest works, the snow doesn’t just disappear. Like an occupying army it kids itself it is making a strategic withdrawal, not experiencing a defeat. It pulls back gradually, grudgingly releasing sods of earth and tufts of rough grass that then start their own process of seasonal transformation and reappear in his summer and autumn pictures in quite different guises.

Purvītis’ work strikes me as very human. We tend to react to artists we like in one of two ways: they either show us the world in a way we have never seen before (these tend to be the ones hailed as geniuses) or they offer us the world in a way that gives us a sense of deepened familiarity and reality. I think Purvītis belongs to the second category. I think it also gives his work a sense of tremendous humanity, even though figures rarely feature.

Purvītis’ greatest gift to Latvian culture may have been his work establishing the first Latvian art academy and the training he gave to numerous younger artists including Padegs and another of my favorites, Pēteris Krastiņš, whose biography was even more tragic than Padegs’ — Krastiņš ended up being shot by the Germans when they decided to liquidate the mental hospital in which he was a resident.

As with many of his contemporaries, many of Purvītis’ works were lost or destroyed during the Second World War. However, a couple of rooms of his work are on permanent show at the Latvian National Museum of Art. Though poorly-lit (if only Latvia had a Kumu) they are worth the small entrance fee in their own right.

Completely lacking ego and ostentation, Purvītis’ work is out of step with the modern age. That may be why I find it so enjoyable and satisfying. [/private_subscription 1 year]

— This is a paid article. To subscribe or extend your subscription, click here.