How to get between points A and B in Estonia? If you are going from Tartu to Tallinn or vice versa, it’s easy; just take the Tallinna-Tartu maantee, that heavy-traffic ridden, accident-inviting highway to hell. But if you are traveling from Tartu to, say, Haapsalu, you must be more creative.

As driver and lead navigator for the family, finding a relatively straight route from one of these locations to the other was not easy. Tartu, the home of Estonia’s oldest university and city of good thoughts, sits almost 200 km directly southeast from Haapsalu, the whimsical seaside retreat of Ilon Wikland and Peter Tchaikovsky.

But there’s no Tartu-Haapsalu road. And I refused to do something so counterintuitive as to make the L-shaped drive west to Pärnu and then north to Haapsalu. No, I was going to drive that damn diagonal straight up to Põhjamaade Veneetsia (“the Nordic Venice” as Haapsalu is called) even if I had to plow through fields or burst through buildings, like Burt Reynolds and Dom DeLuise in “Cannonball Run.”

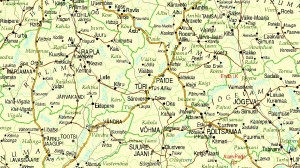

The course I plotted went north past Poltsamaa, southwest at Imavere (pop. 501) to Kabala, then north to Türi. Not like one could tell the difference between any of these places; they were covered by the same seas of fields and dense forests. At Türi, we headed northwest to Rapla, then southwest to Märjamaa, before turning northwest to Koluvere (pop. 404), where we encountered the first sign for Haapsalu. From Koluvere, we headed north to Risti, where we made a final turn west and burned the last 33 km to Haapsalu.

Later when we were having dinner with the film producer who my wife was dispatched to interview, she asked which way we came.

“We took an unusual route,” Epp told her. “We didn’t use any of the main highways.”

“Let me guess,” said the producer. “You took the Tartu-Imavere-Kabala-Türi-Rapla-Märjamaa-Koluvere-Risti-Haapsalu route.”

We looked at each other and realized we weren’t the only creative navigators in Estonia. It was comforting to know that other Estonians who tackled the difficult issue of getting from point A to point B in a country routinely describes as “tiny” had settled on a similar course.

I was happy to zigzag across Estonia because, aside from the elusive Narva, Rapla and Märjamaa were two of the few places in Estonia I had yet to visit. Rapla and Märjamaa. What to expect from this duo? More of the same.

After you’ve visited most of Estonia, you come to understand what an Estonian town or city is made of. Most of them are centered around some body of water, be it a silty river or manicured lake or a broad harbor. The rest invariably grew up like shantytowns around a castle or a railroad stop. Most city streets in Eesti are woven around one heavenly object: a sober-white Lutheran Church that either dates back to or is built on top of the ruins of a place of worship established shortly after the Teutonic conquest in the 13th century.

Beyond the church are main commercial streets dotted with a variety of dwellings. The oldest date back to the 18th century as most of Estonia was trashed during the Great Northern War between Sweden and Russia, while the youngest are postmodern erector sets of metal and glass that would be at home in any city in northern Europe where they sell stuff you really need, like designer jeans.

Outside the city center, you’ll find the brightly-lit evidence of Estonia’s love of consumer goods: supermarkets with names like Säästumarket, Konsum, and Selver; home-improvement oases dubbed Bauhof and Ehitus ABC. Beyond them lie the big box apartment blocks of the Soviet era, the valley of the average Estonian. These Khruschevka pueblos may have once beamed with modernity upon move-in day back in ’62, but today they look worn, and, when you have that many owners living in the same residence, most of them uppity individualistic Estonians who will go to war over whether to paint the front door red or green, then it takes time to settle on a scheme for renovations.

And that’s Estonia. That’s Rapla. That’s Märjamaa, though I admit I was attracted to Märjamaa’s colorful main street with its wooden homes styled in orange and red and blue. It seemed like a special, secret place. A good setting for a great Estonian novel in the vein of Anton Hansen Tammsaare, Oskar Luts, or Andrus Kivirähk.

What can you tell about the Estonian people from a car window? Preciously little, other than they go about their business as if nobody was watching. You forget that most people on Earth remain true to the communities into which they were born. The Raplakad and Märjamaalased are no exceptions. Remember that Maria Tomson, the oldest Estonian on record, spent all of her 112 years between 1853 and 1965 in a small parish in Viljandi county. Century in and century out in, for many Estonians, life is still centered on the Kinder, Kirche, Küche, and Konsum.

Haapsalu, though, is the jewel of them all. It was only my second time there, and already the city moves with me like an old pair of pants. Imagine, ornately decorated, candy-colored homes built around a charming old castle with a face to the islands and the sea. When writers and musicians and handicraft merchants need to get the hell out of the figurative Dodge City, wherever it may be, they pack their bags and head to Haapsalu for a little R&R.

The producers’ house shines as much as a home meant to revive the styles of the 1930s can. With its soft wooden floors, rolling couches, and grand maritime views, one hesitates to even disturb a book from one of the sturdy shelves, nevermind throw a wild house party where half of Estonia and a quarter of Finland docks in the front yard, gets smashed, and then violates the place.

All Estonian conversations flow to the question of languages. “Estonian is difficult.” “It is.” “Do you know any Russian?” “Izvenitsa. Zat knies.” Then there’s that moment when you tell them you’ve been studying Swedish. Speakers of all big European languages turn their heads when you confess that your German is nonexistent, but Jonas bakar bröd, Emil spelar musik, och Anna pratar i telefon.

In the 1930s, Haapsalu used to be known as the “capital of the Estonian Swedes.” Most of them have joined the 9 million Swedes in the mother country, and most of those Swedes prefer not to speak their tongue in the company of foreigners. But I like svensk anyway. In my dreams, I am getting into arguments with Swedish Foreign Minister Carl Bildt on his blog. I’m not there yet, but it could happen. It’s true. The ‘Languages’ section of my CV renders me entirely useless. Except for the English, of course.

The producer, a slender former model in her early 40s, is part Russian, part Estonian. She still has a big toe permanently in Moscow. But she fits in here. It comes naturally. Haapsalu, for all its Scandinavian ambiance, has a distinct tsarist touch. You can walk by the house where Peter “the Great” stayed in 1715. Alexander Gorchakov, state chancellor of Russia from 1867 to 1883, was born here in 1798. It’s a shame the Russians’ leaders are such shitheads, I think to myself as I make my way up a verdant lane in the old city center. They would really enjoy this place.

Could you imagine? Dmitri Medvedev takes an armored train to the old tsarist-era Haapsalu train station where he is met by Toomas Hendrik Ilves in full mulgi regalia. The duo are transported via horse-draw carriage to a local bakery where they are served delicious moskva sai pastries fresh from the oven. From there, the lynx and the bear don old-fashioned swimming trunks for a photo-op and dip at Aafrika Beach before embarking on a public tour of Gorkachov’s birthplace, Peter’s cottage, and Tchaikovsky’s bench. Medvedev compliments the Estonians on their tidy streets and hospitality, while Ilves emulates Halonen and manages to construct some random historical fact into a symbol of good neighborly relations, spicing it up with a Mihhail Veller quote.

But it doesn’t happen. Some of the Russians still haven’t figured out that, though Peter slept there, Haapsalu isn’t “ancient Russian land.” Some of the Estonians are still walking around with their fists in their pockets like an oppressed imperial minority, rather than the overwhelming majority and political masters of the land that bears their name. What a shame, I shake my head and pass an orchard.

Justin Petrone is an American writer living in Estonia and the author of the best-selling travel novel “My Estonia.” He publishes one of the best-written blogs in the Baltic states, Itching for Eestimaa.

Disclaimer:

Views expressed in the opinion section are never those of the Baltic Reports company or the website’s editorial team as a whole, but merely those of the individual writer.