Like Jason's choice of Glauce over Medea, Estonia may find that forgoing economic stability measures for the sake of entering the eurozone may have been a mistake.

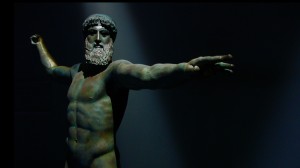

Most Greek tragedies center on a tragic hero: a figure of noble standing who eventually falls victim to an inherent tragic flaw such as arrogance or hubris. That downfall, and the suffering it causes to the hero and others, cautions the theatergoer about displaying similar character flaws of their own.

In the theater of euro politics, Greece is the most cliché example of the tragic hero. Greece’s noble standing is that of being in the coveted eurozone. Its tragic flaw was pretension in concealing an untenable budget deficit. The downfall is a sovereign debt crisis that has wrecked the Greek economy. The crisis has tested the solidarity of the eurozone, rattled the stability of the currency, and brought doubt to the euro’s future.

So, in this analogy to the eurozone, will Estonia, who is seeking to adopt the euro currency itself, be part of the tragedy and succumb to Greece’s own downfall?

Estonia has made tremendous progress in meeting the Maastricht criteria for joining the single currency, the euro. During the financial crisis, the government, like the one in Latvia, passed several tax increases and slashed spending. Now, its deficit and percentage of public debt are some of the lowest in Europe. Economists predict that the country will join the euro-zone at the beginning of 2011. It would be the first Baltic country to reach that milestone.

Nevertheless, Jürgen Stark, a German representative of the European Central Bank’s executive board, has reportedly argued against Estonia’s membership. The country has met the requirements for membership, he said, but the situation in Greece is causing the Central Bank to rethink the admission criteria. He would like to see economic sustainability and GDP per capita metrics included.

Euro members (especially Germany), then, may not be as eager to allow another risky state into the club without some rule changes. This may make entry harder for Estonia.

But Estonia still has a big ally on its side: the European Commission. The Commission has supported Estonia’s bid repeatedly through positive progress reports. A recommendation by the Commission and the European Central Bank whether Estonia can adopt the currency is expected mid-May. Many still believe it will be positive despite the Greek crisis, because the Commission can likely sway the more conservative central bank to support Estonia. But a statement from the EU’s commissioner for economic and monetary affairs, Olli Rehn, claiming Estonia is at “high risk” of being rejected for euro membership means accession is not a done deal. Nevertheless, it’s unlikely the Commission will stall Estonia’s progress — it would set a bad precedent for other countries seeking to adopt the currency. Plus, it would be seen as punishing Eastern Europe for the mistakes of Southern Europe.

Overall, Greece will likely have little impact on Estonia’s bid. The Council’s Economic and Financial Affairs Council, or ECOFIN, will likely vote on Estonia’s membership in mid-July.

But, will Estonia have learned anything from Greece? Is Estonia going to be another tragic hero?

Of course, it is too early to tell what will happen to Estonia after it adopts the euro. One thing is for sure, Estonia will not have the same problem of credibility that Greece had. Greek officials lied about their public finances for years to qualify for euro membership. But Estonia’s finances are under such close scrutiny by the EU that such a problem doesn’t exist. Prime Minister Andrus Ansip, the finance minister Ivari Padar, and a host of other surrogates have mounted an optimistic charm offensive to alert European officials that they are ready for euro membership and they are certainly not Greece.

Estonia does risk critically jeopardizing the euro, though. Moody’s, Standard and Poor’s, and Fitch — the three most important credit rating agencies — have improved their ratings of Estonia in the last few months, and Estonia’s rating is above those of the other Baltic states. But the news isn’t all positive. Fitch, for example, doubts the long-term sustainability of the country’s economy inside the eurozone.

Internal devaluation—the tax hikes and spending cuts—has produced high unemployment and wage decreases, but has prevented Estonia from devaluing its currency (losing its euro peg). The measures have been harsh on the small Baltic economy, but paid off in the end as Estonia approaches euro membership. But these were measures taken specifically to counteract the financial crisis and not a part of a medium or long-term strategy. If Estonia’s internal devaluation is prolonged, unemployment will remain high and inflation will increase. Entering the euro will make actual devaluation to reverse the downturn impossible.

Estonia’s high inflation may be the biggest cause for concern. Inflation sharply increased after Estonia’s admission to the EU, when gross domestic product rapidly grew. Only because of the decline in GDP during the financial crisis has it recently come under Union limits. But new projections of Estonia’s higher-than-expected GDP growth could start the whole cycle over again. But this time, Estonia might already be inside the eurozone; the Central Bank cannot easily target monetary policies to fight the inflation of a single state.

Estonia, then, could emerge the tragic hero in this drama after all. Its noble standing is the pride of place (economically) it holds above the other Baltic states. Its tragic flaw would be arrogance in believing it was ready for the euro too soon. The downfall would be a disaster on a scale as the one in Greece.

The situation in Greece will certainly raise doubts about Estonia’s admission to the euro. Estonia’s downfall, if it occurs, will not be because of Greece though, but ultimately from its own flaws. The Baltic states, particularly Estonia, should worry less about adopting the euro and more about economic and financial stability; adoption of the euro will come naturally thereafter. Don’t try to be a hero.

Michael G. Dozler is a graduate student of international affairs who received a Fulbright research grant for study in Latvia.

Disclaimer:

Views expressed in the opinion section are never those of the Baltic Reports company or the website’s editorial team as a whole, but merely those of the individual writer.

wow, This was the most absurd article I’ve read this week..

well done, nothing like a full article telling someone not to “be a hero” when the decision is clearly NOT in Estonia’s hands anymore…

Really the situation in European Union is quite dangerous, due to the debt crisis in Portugal, Greece and Ireland. The European Comission should take care about this.